In my years working with children, students have done many things to me. I have had things thrown at me - accusations, insults, paper, pen lids, books, rubbers and blu-tack. I have been told to fuck off. I've been threatened with fists, knives, steel bars and bike chains. I've been punched, kicked and head-butted.

Working in Special Needs Education, inner city comprehensive schools and in areas of social deprivation, these incidents are an occupational hazard. They are not acceptable but they happen: They are imaginable.

But what if I told you that a student once pissed on me? Is that imaginable?

For obvious reasons, I'll change her name. I'll call her Lola because I am playing with you. A student, a girl student, gave me a golden shower. And the name I choose for her is Lola. Imagine that.

Lola was not a nymphette. In fact she was as far from a nymphette as it is possible to imagine. I want you to imagine that. She was tiny, stick thin, painfully bony. That is my anti-nymphette. Yours might be different.

She did have a crush on me though, and around school she would invariably be attached to my arm.

My role in school was varied. I was a counsellor, a social worker, an amateur speech therapist, a play therapist, a drama therapist. I was also a climbing instructor.

We took groups of a dozen kids climbing two or three times a week. We climbed outdoors in the Peak district, North Wales, the Lakes and around the county. We did day trips and residentials. We hostelled and climbed, we camped and climbed.

If the weather was bad we climbed at a local wall. I also worked there at weekends, and the familiarity I had around the place helped the students to feel secure.

The whole point of the climbing was to build self-esteem. All of our students had been rejected by schools; thrown out for bad behaviour. They had been labelled bad. Many of the children had suffered from abuse and those that weren't abused were neglected. They all had language and literacy problems, found communicating a problem. And when adolescence hit they were struck down with depression; depressed because they recognised they could not be like their 'normal' friends.

Lola was all of these.

Louis Sachar wrote that, " if you take a bad kid and make him dig a hole every day, you come out with a good kid." This is a bad mantra. This is how you break people. These kids were already broken.

We took painfully shy, emotionally delicate kids, with a Statement of Special Educational Needs and medical files as long as the arm to which they clung. We took those children and pulled, hauled, dragged, cajoled and persuaded them to the top of vertical walls and cliffs. And the more we did it the stronger they became, physically and emotionally.

The climbing wall was cold that day. Our breath hung in the air. It was indoors, but the ceiling was 20 metres above us and the heat sat up there somewhere. In every way this was an indoor wall, the anti-crag. Outdoors you get colder as you climb higher. At the indoor wall the temperature is proportional to your height. Many of our students never noticed. They remained in the cold air, near to the ground, because despite our coaxing, some children would not let go of the security of the cushioned floor.

We explained that they were safer the higher they went. That it was the landing on the floor that hurt, not the falling. That, in fact, falling felt a little like flying. It could be fun. That, yes, I was qualified. Yes, the knot was right. Yes, the equipment was safe.

Every one of them had a go that day. Although the concept of having a go varied significantly. That is what we call differentiation in education. Every one of our students had a go. For Lola, this meant they climbed and reached the top. For others, it meant that they had got off the ground without us pulling on the rope. Others were hauled like a sack on a crane. For several, having a go meant taking their hands out of their pockets and allowing someone to put a harness on them, fit a helmet and then remove them again. Every time we took students climbing, every single one of them had a go.

Lola was a good climber. She was the weight of a balsa model and she had the flexibility of youth. She was also brave. Unfazed by the height, she would push and pull and reach to her limits. She would fall off. At the time, my youthful ego put her success down to her trust in me. I believed that she trusted me, that I was the only person she trusted. If I told her she was safe, she believed me. That is what I believed.

Looking back now it could just as easily have been different. She was abused as a younger girl. Emotionally damaged beyond repair. She clung to me physically because physical relationships with adult men were the only relationships she knew. She was offering herself to me. She would have let me because that was her learnt behaviour. And she fell off not because she trusted me, but because her self esteem was so low, she valued herself so little, that falling of didn't matter.

Each student had a go, and that takes a while. For Lola the experience was frustrating. She was the only one climbing, the others simply held the wall, wore a harness, hung on the rope. Each of these attempts taking up more and more time. Lola wanted another go. She wanted to climg high, feel the warmer air, get away from the ground to where she was safer. Looking back I can see why she liked it. Her natural instint was to give herself to adult men, like me. We taught her a different way. We didn't abuse her trust. But this made her uncomfortable. It destabilised her world view. It made her nervous and embarrased and hurt and rejected. No wonder she wanted to climb out of that world to a place where the air is warmer.

We gave her one last go. The others were ready to leave quickly. They watched Lola climb while they stood by the door with their helmets and harnesses ready to hand in. Lola climbed easily, gracefully. She had a rope that attached her umbilically to me, but the rope was loose. It was her own strength, her own will that took her up, up and away.

And while I stood beneath her, barking instructions to the group to make sure we were ready to go promptly, Lola pissed on me. From a height of 15 metres she emptied her bladder onto me with no word of warning, no shout of "below" that we had taught, the climbing equivalent of the golfers "fore!". No one said a word.

I stood aside and she continued to shower the matting where I had been. It splashed my shoes and it was in my hair. And no one said anything because it would have been like asking a stab victim why they were bleeding. She couldn't help it. That's what I believed then. Now, I'm not sure she wasn't getting me back in some way.

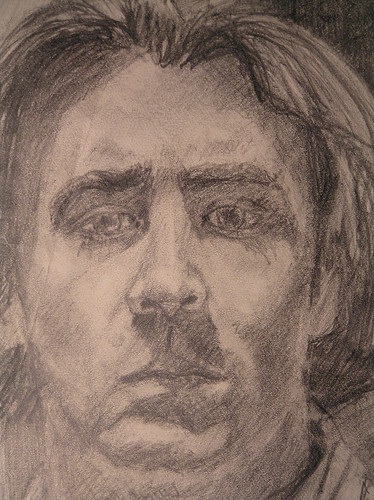

Lola

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Tell me what you think