Rob Cooper

Postgraduate Certificate for Educational studies:

Education for Citizenship

Module 2

Voicing Concerns:

From exclusion to engagement

Citizenship Education for SEN Students

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Roy Leighton, of Independent Thinking Ltd, who at a training conference four years ago reinforced my faith in a creative approach to teaching and as a consequence of this made me realise that I was in the wrong job.

Contents

| Abstract……………………….. | 4 |

| Introduction…………………… | 5 - 6 |

| Literature Review……………. | 7 – 10 |

| Methodology…………………. | 11 - 13 |

| Action and Findings…………. | 14 - 16 |

| Analysis and Discussion……. | 17- 21 |

| Conclusions………………...... | 22- 23 |

| Bibliography………………...... | 24- 25 |

| Appendix 1 – List of Learning difficulties and Disabilities | |

| Appendix 2 – Student participant literacy levels | |

| Appendix 3 – Intervention day activities outline | |

| Appendix 4 – Video activity questions | |

| Appendix 5 – Student response transcripts | |

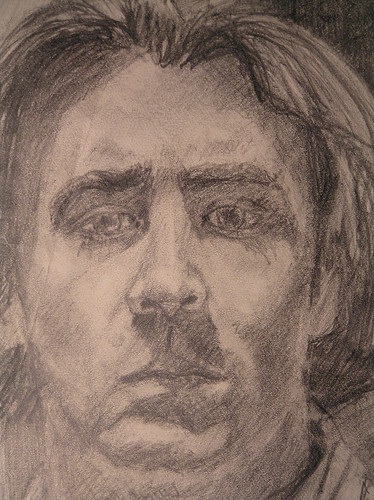

| Appendix 6 – Citizenship topic images | |

| Appendix 7 – Full data sheets | |

| Appendix 8 – Action research project framework | |

Abstract

My Action Research Project aimed to discover the local, national and global Citizenship concerns of students with Special Educational Needs (SEN) using creative teaching strategies based on Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences.

Data was collected through a non-verbal, interactive questionnaire, teacher observation, witness statements and video.

My main findings are that my students are significantly more concerned with global rather than local or national issues. They are interested in technology but are worried by diversity. They regard politics as boring. They are able to engage thoughtfully with issues if material is presented appropriately.

Introduction

I am Head of Citizenship at a Special school. All students have a statement of Special Educational Needs (SEN). For a full list of their Special Needs, see appendix 1.

It has been said that action research starts as a “’living contradiction’; that is, feeling dissonance when we are not acting in accordance with our values and beliefs.” (McNiff, Lomax and Whitehead, 2003 :59) This seems especially apt.

There is a clear contradiction between inclusive education and special needs education. I am acutely aware of the tension between my role as Head of Citizenship where I represent the values of diversity and inclusion and have a responsibility to promote community cohesion, and our status as a special school where potentially we are a contributory factor in the marginalisation of our students from mainstream society.

Social Exclusion and its impact upon the local, national and global citizenship concerns of my students is therefore the first conceptual framework of this research project.

There is also contradiction in the concept of student voice for students with communication difficulties. If teachers are to respond quickly to contemporary issues and deliver relevant lessons for the students in their classes, there has to be some kind of dialogue between themselves and young people but with SEN students this dialogue is difficult to initiate.

I regard myself as an advocate for the Special Needs Students that I work with, speaking on their behalf, but I also have a duty to ensure they are given the skills and opportunities to speak for themselves.

Consequently, Student Voice is the second conceptual framework of this research project.

I was fortunate to attend a conference recently at which Roy Leighton was the guest speaker. I was very much looking forward to hearing him again, as the first time I heard him speak had a profound effect on my career pathway. He opened with a point that can be easily lost amongst all the day to day practicalities of teaching in a busy school: “It’s the brain, stupid!” (Leighton, 2009)

I find it incomprehensible that as a PGCE student I received no training in brain structure and how we learn, despite the fact that this incredible organ should be the teachers’ single focus of attention. The workings of the brain and in particular how people learn, takes on extra significance in my working life when we consider two facts: Traditional teaching uses language as the primary means of communication; and the students at my school have significant language and communication difficulties.

How a creative approach to teaching and learning enables Special Needs students to access the Citizenship curriculum represents the final conceptual framework of this research project and is the third of the contradictions that have led me here.

Not only do my students face the everyday concerns of typical teenagers living in Britain today, they also have to face the specific concerns related to their disabilities and learning difficulties. I am committed to ensuring that our Citizenship programme should allow them to identify and explore those concerns but I am not disabled, I do not have learning difficulties and I am not a young person growing up in 21st century Britain.

Clearly, I am not the best person to decide what my students concerns should be.

Literature Review

Social Exclusion

Social Exclusion is, “a shorthand term for what can happen when people or areas suffer from a combination of linked problems such as unemployment, poor skills, low incomes, poor housing, high crime environments, bad health, poverty and family breakdown.” (www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk)

The specific effects of Social Exclusion on young people are wide and varied but generally, “it can significantly damage their physical, mental and social development.” (Ruxton, 2001, p.71)

I would contend that Social Exclusion should also include a more general acknowledgement of the marginalization of young people that we witness today.

The Times newspaper recently published an article under the headline, “Most adults think children ‘are feral and a danger to society’.” (www.timesonline.co.uk) and The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) suggested that the UK government should be, “Taking urgent measures to address the intolerance and inappropriate characterization of children, especially adolescents” (UNCRC, 2008).

There is clearly a danger that young people are increasingly likely to be marginalized from society simply because they are young people. In fact Goldson goes one step further and talks of the, “Demonization of Children.” (Goldson, 2001: 34)

Lansdown lists specific examples of how young people have been excluded from mainstream society: “The introduction of powers to impose child curfews, the refusal of many shops to allow children in and the decision by the Millennium Dome to refuse entry to the under 16s if they are not accompanied by an adult.” (Lansdown, 2001: 92)

Learning Difficulties and Disabilities are also a factor in this wider sense of marginalization. As Ruth Marchant points out, “Disabled children face major barriers to being included as equal members of society.” (Marchant, 2001: 217)

My students all have Learning Difficulties and Disabilities and are, “more likely to be brought up in poorer socio-economic households than non-disabled children.” (HM Treasury, 2007: 8) They are also young people. For these reasons, I conclude that the students I work with are at significant risk from Social Exclusion and I believe that Citizenship Education, especially through Student Voice, has a special and significant role to play in helping them to identify and face up to the challenges posed by their status, or lack of it.

Student Voice

On the status of children in society, Wendy Rogers identifies two dominant political discourses at play: The discourses of welfare and of control (Rogers, 2001: p.30). Each frames social and educational policy as being done to children.

These ‘traditional’ discourses are being challenged by a new discourse which sees the status of children shifting from that of recipients to participants (Roberts, 2001: 64). In this new discourse of participation, “children do have the right to be heard” (Thomas, 2001: 105) and it manifests itself in schools as Student Voice.

According to Jean Ruddock Student Voice is, “the consultative wing of pupil participation” (Ruddock, 2005: 1) and is born out of Article 12 of the 1990 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which provides that:

“States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.”

Whilst Benton et al (2008), Roberts (2001) and Thomas (2001) all identify this shift, Student Voice is still very much in its infancy. In their response to the UK’s 3rd and 4th reports on The Rights of the Child in 2008, the UN expressed concern that, “Participation of children in all aspects of schooling is inadequate, since children have very few consultation rights” (UNCRC, 2008: 1) Clearly, this policy shift has not yet translated into practice.

Ruddock argues that Student Voice provides an opportunity, “to hear from the silent – or silenced”. (Ruddock, 2005: 2) Given that my students are at significant risk of being silenced through social exclusion, the potential benefits are great. However, Ruddock also points out that it, “assumes a degree of social confidence and of linguistic competence” (Ruddock, 2005: 2) and so in my professional setting, the challenge is to find a way to listen to students who either have no voice or they have a voice that is difficult to hear.

Creativity in the Classroom

Education has been a key public and political issue since at least the 1944 Education Act when Education became one of the three pillars of the new welfare state (Tomlinson, 2001: 9) and as such it is always subjected to pedagogical challenge. Everyone, it would appear, has an opinion on education.

Sir Ken Robinson verbalises one such opinion which seems to be gathering momentum: our education system fails to prepare children for the 21st century world that they will grow up in (Robinson, 2006 and Robinson, 2008). Something needs to change and recent government policy reflects a desire to affect this change.

The genealogy of this desire begins at policy level with the government green paper, Every Child Matters (ECM) in 2003, and the New Secondary Curriculum (2007) and The Children’s Plan (2007) that emerge from it.

With its five outcomes: be healthy, stay safe, enjoy and achieve, make a positive contribution and achieve economic well-being, ECM directly informs the New Secondary Curriculum which, “should enable all young people to become: successful learners who enjoy learning, make progress and achieve; confident individuals who are able to live safe, healthy and fulfilling lives; responsible citizens who make a positive contribution to society.” (QCA, 2007: 7) Significantly, embedded within the New Secondary Curriculum as a cross-curricula dimension is creativity, which Sir Ken Robinson identifies as the central vehicle for affecting change: “Creativity now is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status.” (Robinson, 2006)

Whilst, “The literature in the area of ‘Creative Learning’ generally, is patchy and emergent” (Craft et al, 2006: 35), Peter Woods defines it as being “characterized by innovation, ownership of knowledge, control of teaching processes and relevance to the learner” (Woods, 2001: 75). In government policy, Creative learning manifests itself as Personalised Learning, which has, “Achievement, aspiration, inclusion (…) and accountability” (West-Burnham, 2008: 8) amongst its components.

Personalised Learning is at the heart of the government’s vision for education in the future: “We intend to create a system in which no matter what level a young person is learning at, and no matter what their preference for style of learning, they will have access to a course and to qualifications that suit them." (DCSF, 2009: 4)

“Style of learning” is a key element of Personalised Learning. David Milliband talks of Personalised Learning as requiring strategies that “accommodate different paces and styles of learning.” (Milliband, 2004) Both cases refer to pedagogical principals rooted in the theory of Multiple Intelligence developed by Howard Gardner in his book Frames of Mind (1984)

Whilst Multiple Intelligences and learning styles, or the “crude reductionism of specific learner types” (Milliband, 2004), that leads to the VAK activities commonly seen in lesson planning, are not automatically synonymous with creativity, Gardner’s is a key text within this particular framework.

Methodology

Howard Gardner notes that, “Much of teaching and learning occurs through language” (Gardner, 1984: 78) which is a problem for students whose literacy levels are very low compared with national expectations (See Appendix 2); the traditionally dominant mode of education actually represents a barrier to learning. Therefore the main feature of my methodology is the restricted use of data collection methods that make linguistic demands of my student.

Instead of using traditional student questionnaires which would have been both too difficult for students to complete independently and too unwieldy to manage if administered with one to one support, I designed a series of activities which can be regarded as a non-verbal, interactive questionnaire. Each activity represents a single question where students respond to a set of images via mainly non-verbal means based on Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences. For fuller details of the intervention activities see appendix 3.

A class of 10 year 9 students took part in the questionnaire which was administered on an intervention day held in a gym with appropriate audio-visual facilities. The class was chosen as being representative of as wide a range of socio-economic backgrounds, and learning difficulties and disabilities as possible within a single class.

Of the 12 activities planned, only 10 activities were completed due to time constraints. 6 asked the students to identify sets of images as being positive, negative or neutral. 2 asked the students to rank order sets of images. 1 activity asked the students to match images to pieces of music and a final activity asked students to match emoticons to statements about their local, national and global communities. Of the ten activities run, all but one asked for non-verbal responses.

For most of the activities students were asked to respond in terms of whether they felt positive, negative or neutral about the images presented to them. Positive was introduced as an image that they would like to learn more about. Negative was an image that scared them. A neutral image was an image that bored them or one they had no opinion on. These terms were simplified further to good, bad or boring.

In response to some sets of images, students were asked to rank order the them according to levels of interest, but these responses were framed in a similar way: Good through to bad.

The simplicity of the terminology was intended to reduce to a minimum the possibility of misunderstanding but misunderstanding could not be eliminated entirely. One reason for this is that the citizenship topic to which each image was attached was open to a degree of interpretation.

Student responses were recorded by the Learning Support Assistants (LSAs) on data collection sheets specific to each activity.

One potential weakness of the data collection methods comes from this necessary simplification in that it denies the possibility of any alternative, appropriate responses. To counter this, I chose to collect additional data through staff reflection, video recording and photographs.

Students were encouraged to use a video camera and an LSA was assigned to help them operate this. This gave individual and paired students the chance to respond either to a range of predetermined questions (Appendix 4), or to respond to the activity just completed. This data would also help me to determine the effectiveness of the teaching methods not just through the content of their verbal responses but also in the non-verbal signals of their expressions, gestures and body language. These kinds of responses would also be recorded via reflections from the staff involved and through photographs. Cameras were made available for staff and students to use. Examples of this ‘soft’ data can be found in appendix 5.

Students were also provided with drawing equipment and encouraged to draw their responses to the activities. Whilst this proved to be an effective classroom management strategy between activities, the data it provided was less useful, being too difficult to decode.

In working with students with Learning Difficulties, there were clearly ethical issues to consider. In the planning stage, I consulted with our Assistant Head to check that my proposition was reasonable. I spoke directly to the class about the intervention day prior to the event, clarifying what they would be doing, why they were doing it and giving them a clear opportunity to withdraw themselves. I also sought written permission from parents and carers via letter using simplified language as many of them also have learning difficulties. One student was withdrawn from the event at the request of the parents.

Our students very often find a change of routine difficult to cope with and so whilst I was keen to design an inspiring and creative intervention day, I was also well aware that I would have to carefully manage the stress and anxiety that such a day may cause.

I designed the layout of the gym area so that each student would have an identified intrapersonal area. This would give them a refuge to return to and it was made clear that they could sit out any of the activities if they felt they were too challenging. Several students took up this option and this explains the varying number of responses recorded for each activity.

As well as these private spaces, I also provided interpersonal spaces with activities and distractions related to the day. In the setting up period between activities, students were encouraged to sit in these communal areas and interact with each other in this space. The drawing and video activities were located here.

I also made it clear on the day that students could return to timetabled lessons at any moment if they chose to do so. One student on the day took up the option to return to class, finding the day too difficult.

Action and Findings

Each activity had two aims. Firstly, it aimed to find out the global, national and local Citizenship topics of interest to the students both in positive and negative terms through consultation and participation. The results would hopefully allow me to identify areas of interest, fear and anxiety and these results could later be used to revise the key stage 4 curriculum to make it relevant to the students.

Secondly, the data would allow me to analyse which delivery methods were most engaging and that enabled the students to participate in a dialogue about the future content of their Citizenship programme most effectively.

The majority of activities were based on sets of 9 images that represented one of each of the chosen Citizenship topic areas; Environment, Animals, Technology, Poverty, Law, Freedom, Politics, Diversity and Conflict. These represent a broad a range of citizenship topics but I acknowledge that they are largely arbitrary and not comprehensive. The images used can be seen in appendix 6.

I was clear from the start that I wasn’t simply looking for the images that elicited a positive response. The negative responses to images might reflect common concerns and misconceptions that would need to be addressed in curriculum time.

The full data sheets showing the results from all activities can be seen in appendix 7.

Main Findings

Whilst the activities simplified student responses as much as possible, the different methods for collecting responses seemed to affect the outcomes. In the 6 activities that asked students to decide whether they thought images were positive, neutral or negative, technology was clearly perceived as being positive. Images of law and diversity were seen as equally negative. These results broadly matched my expectations of the attitudes of typical teenagers.

In the 2 rank order activities, politics was perceived most negatively with diversity also seen as negative. Freedom was seen in the most positive light in these activities. Some of the findings from these rank ordering activities seem to contradict each other and suggest that the activity represented something of a barrier to the students understanding.

In the musical intelligence activity, animals and politics were chosen most often, although whether any conclusions can be drawn from this will be discussed in the next section.

The final activity shows that students are clearly more concerned by global issues than local and national issues and may reflect a lack of engagement with communities closer to them as a result of various forms of social exclusion. Alternatively, students may be influenced by high profile international news stories in the media at the time of the intervention.

In terms of the activities and teaching methods, it was clear that the students responded positively to the day as a whole and were boosted by the sense of empowerment that came from being consulted in this way. The day was very demanding on them however, with most students exercising their right to sit out at least one activity.

Students were engaged by the use of interesting and challenging images. The kinaesthetic activity where students expressed an opinion through body shape proved to be the most difficult for students, challenging the perception that SEN students respond best to kinaesthetic activities. Other practical activities were popular however.

it is clear that proper consultation of SEN students makes extraordinary demands on the school in terms of resources and time. This was in essence a 12 part questionnaire that could be administered to large numbers of mainstream students in a very short space of time. With SEN students, the 12 questions had to be reduced to 10 questions and took up an entire day and required a huge amount of planning and extra resources. This is also very demanding on the students who were actively and energetically involved in learning for 5 hours in total. In the case of one student, the demands were too great and they returned to class. These are important considerations for teachers and senior leaders to take into account.

Analysis and discussion

Figure 1 shows all student responses from activities 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 12. Negative responses were given a value of -1, positive responses +1 and neutral responses 0. The totals for each topic image were then added together across the 6 activities. The adjusted total represents these totals minus the highest and lowest scoring images from each topic. Removing the extreme results helps negate the effect of strongly emotive images.

Figure 1 suggests that students are interested in technology, are bored by politics and have a negative attitude to freedom and diversity.

Figure 2 presents the average results from activities 2 and 4 where students discarded images in rank order, with the intention of retaining the image that was of most interest to them. This image was given a value of 1. The first image discarded was given a value of 9. Therefore, the lowest values represent images perceived most positively. Here, freedom seems to be the most interesting topic to students. This contradicts figure 1. Similarly, whilst politics is clearly boring in figure 1, in figure 2 students seem to have a strongly negative response to politics.

There are two possible explanations for these contradictions. In rank ordering activities like activities 2 and 4, where 1 represents a positive response, a value of 9 can be interpreted as representing either a negative or a boring response. So, whilst low numbers can be regarded as being a fairly accurate reflection of an overall positive response, the meaning of higher values is less clear. So, figure 2’s results may support the findings from Figure 1 with politics again being regarded as boring rather than negative.

The second possibility is that a rank ordering activity is much more complex and students with dyslexia and similar organisational difficulties may be disadvantaged by this learning activity.

In figure 2, poverty, which is seen as very positive in activity 2 and either boring or negative in activity 4, produces conflicting results within the same data collection method. This may be because the students were more interested in the image representing poverty in activity 2 because a child was depicted in it. If more rank ordering activities had been conducted then it could have been possible to eliminate the extreme results as done for figure 1 and the effect of over emotive images could have been countered.

In activity 8, students were given a choice of images after hearing each of 6 pieces of classical music. The music was intended to represent either positive or negative moods, with the pieces alternating between the two. However, during the activity it was clear that students interpreted the moods differently and therefore the data from this element of the activity has been ignored. Figure 3 records how many times each image was chosen. The music seemed to influence which images were chosen – no student remained rooted to one image – but how the music was interpreted by each student is difficult to say. The data does however indicate which subjects students were moved by, either positively or negatively.

What is interesting here is that technology, which was seen as the most positive topic from figure one, seems to be the least interesting here. This is surprising as the specific image from activity 8 is of a futuristic mobile phone, a subject that would be expected to appeal to stereotypical teenagers. The image of a mayor (politics) was the most popular choice during this activity. These responses appear to contradict expectations. It is possible that the students perceived all of the music, which was classical music, to be negative or boring and that therefore these results should be interpreted differently. Unfortunately, this method was only used for one activity and to make any concrete claims one way or the other would require further investigation.

Figure 4 shows the results of Activity 11 which was an interpersonal activity. Pairs of students interviewed each other, asking their partner to point to one emoticon on a sheet of 30 such images to represent their feelings towards statements read to them. The clear conclusion from this chart is that students have a far more negative attitude towards global issues. More investigation needs to be conducted to ascertain exactly why, but this may in part be due to media coverage of global issues at the time of the intervention: Conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq, and Swine Flu were the main stories in the weeks leading up to the event. An investigation into the relationship between media headlines and current student concerns on the next action research spiral would be interesting.

Figure 4 also shows that students appear to be bored with local issues. One possible interpretation is that the students feel excluded from their local communities and are therefore disinterested as a result of this lack of ownership. This is a disturbing finding that demands further investigation.

In terms of the soft data collected through video, photograph, observation and witness statements, it is clear that students were motivated by the intervention day. Students enjoyed most activities and whilst a lot of fun was clearly had, the thought that students put into their responses and the incidental conversations and comments that students made clearly suggests that they were actively engaged in their learning.

Conclusions

The predominantly negative response to depictions of diversity, whilst not surprising, is nevertheless worrying. In video responses and in conversation, it was apparent that there is confusion and prejudice, particularly with students using the terms terrorist and Muslim almost interchangeably and also in the use of homophobic language. This action research has highlighted a need for the new Citizenship programme to address these misconceptions and prejudices.

Another finding of this research is the mainly disinterested attitude of the students towards politics. If Citizenship Education is to engage students with local, national and global politics then this also needs to be addressed.

This research suggests that SEN students have little interest in their local communities and that this lack of engagement may be a symptom of social exclusion resulting from their status as young people in special needs education.

On the positive side, it was clear following my intervention, that students could be challenged to think and were enthused by teaching methods that activated all of their intelligences. It was interesting to observe that kinaesthetic activities were not widely enjoyed, with many students finding using their bodies too embarrassing. Kinaesthetic activities are often regarded as a panacea for students who struggle with literacy, but this seems not always to be the case.

Visual Intelligence activities were very successful and all students responded positively and thoughtfully to the images presented. Future schemes of work will need to make much more use of visual resources to initiate discussions.

I can foresee two possible challenges on the next spiral of research. Firstly, effective Citizenship teaching for SEN students requires that students are given the time to express opinions and have an input into the direction of their own learning The students who took part in this intervention expressed their appreciation at being involved in the planning of a curriculum and their attitude and behaviour reflected this. There may be a clash with senior leadership in terms of what planning for this style of teaching and learning might look like. Lesson plans that are less descriptive in terms of actual content, because the point of the lesson is to allow the students to direct the learning, may well be at odds with school planning policy.

Secondly, consultation with SEN students places huge demands on schools in terms of resources and time, and in the current economic climate these demands pose a significant threat to that consultation process.

Students came up to me for a week after the event thanking me for the day and saying how much they enjoyed it. I conclude that SEN students do have views that need to be heard, but senior leaders will need to make the appropriate resources available and this requires their full commitment to Citizenship Education.

Bibliography

Benton, T., et al, 2008. Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study (CELS): Sixth Annual Report – Young People’s Civic Participation in and Beyond School: Attitudes, Intentions and Influences, Nottingham: DCSF Publications.

Craft, A, Cremin, T, Burnard, P, and Chappell, K, 2007. Teacher stance in creative learning: A study of progression. Journal of Thinking Skills and Creativity, Open Research Online: Open University

Goldson, B., 2001. The Demonization of Children: From the Symbolic to the Institutional. In Foley, P. Roche, J and Tucker, S. (eds.) Children in Society: Contemporary Theory, Policy and Practice. United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan

HM Treasury, 2007. Policy Review of Children and Young People: A Discussion Paper. London: HM Treasury

Lansdown, G., 2001. Our Bodies, Ourselves? Mothers, Children and Health Care at Home. In Foley, P. Roche, J and Tucker, S. (eds.) Children in Society: Contemporary Theory, Policy and Practice. United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan

Leighton, R., 2009. (9th July) The blocks to lifelong learning. The Derby Conference Centre

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project. London: RoutledgeFalmer

Milliband, D., 2004 (18th May). Choice and Voice in Personalised Learning. DfES Innovation Unit Conference

QCA. 2007. The National Curriculum. London: Qualification and Curriculum Authority

Robinson, K., 2006. Schools Kill Creativity. http://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity.html

Robinson, K., 2008. The Education System Needs a Radical Shake up. New Statesman; 28th July: 4-5

Ruddock, J., 2005. Pupil Voice is here to Stay. London: Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

Stainton Rogers, W., 2001. Working with Disabled Children In Foley, P. Roche, J and Tucker, S. (eds) Children in Society: Contemporary Theory, Policy and Practice. United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan

Tomlinson, S., 2001. Education in a Post-Welfare Society. Buckingham: Oxford University Press

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2008. Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 44 of the Convention: Concluding Observations – United Kingdom and Northern Ireland.

West-Burnham, J., 2008. Leadership for Personalising Learning, National College for School Leadership

Woods, P., 2001. Creative Literacy. In Craft, A, Jeffrey, B, and Liebling, M, (eds.), Creativity in Education, London: Continuum, 62-80

http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/social_exclusion_task_force/context.aspx 26/09/09

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/education/article5167811.ece 17/11/08